What we feel and what we know, 2024

Verein für Originalradierung München e.V., Germany.

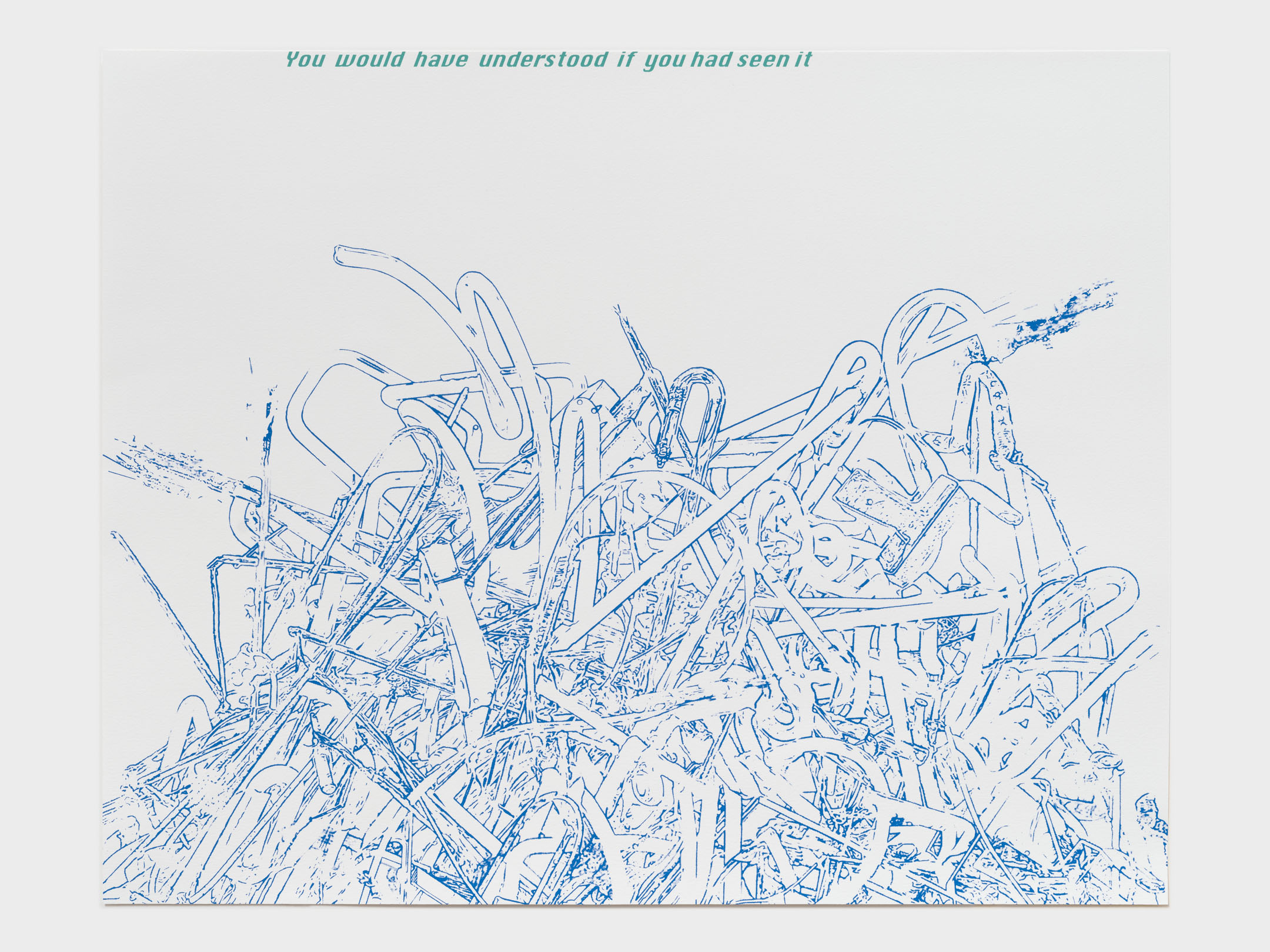

fig 1. Installation view main gallery

fig 2. Installation view

fig 3. Installation view

fig 4. Installation view

fig 5. Installation view

A two-person exhibition with works by Julia Powles and Peter Westwood. This exhibition was also accompanied by a satellite project at Boutwell Schabrowsky Gallery, Munich, Germany.

Julia Powles and Peter Westwood are interested in how knowledge is formed. For both artists knowledge, or understanding, is something that must necessarily remain only partially articulated - semi-spoken words and ambiguous motifs are offered up for others to interpret and complete. These artists would suggest that knowingness arises within our bodies through experience and sensation as much as it is grasped within our minds.

While we can draw visual connections between the use of imagery and text in both Powles and Westwood’s works, less obvious is the way that they both mine their childhoods and unconscious selves for subject matter. The types of knowledge and understanding formed via our childhood experiences is uniquely felt and often profound in one’s life, as it comes from a time when our encounters are both bodily and psychologically felt, yet unexamined.

Language is an imprecise tool, and how well we can ever communicate our thoughts and ideas to others is uncertain. Devising text as tapestries, Powles formed sentences that are personal, having surfaced from specific events in her life – but while her sentences are particular, they correspondingly suggest the universalism of a homily like` ‘home sweet home’. Made from thread that is left over from other people’s projects, Powles never plans these works; the ordering of the words and final sentence arises while she is making them, allowing the very slowness of the process to help form her thoughts into words. Similarity her large-scale textile works have the appearance of formal abstraction yet are in fact derived from Venn diagrams of her complex family structure, again surfacing through conscious and unconscious awareness’s.

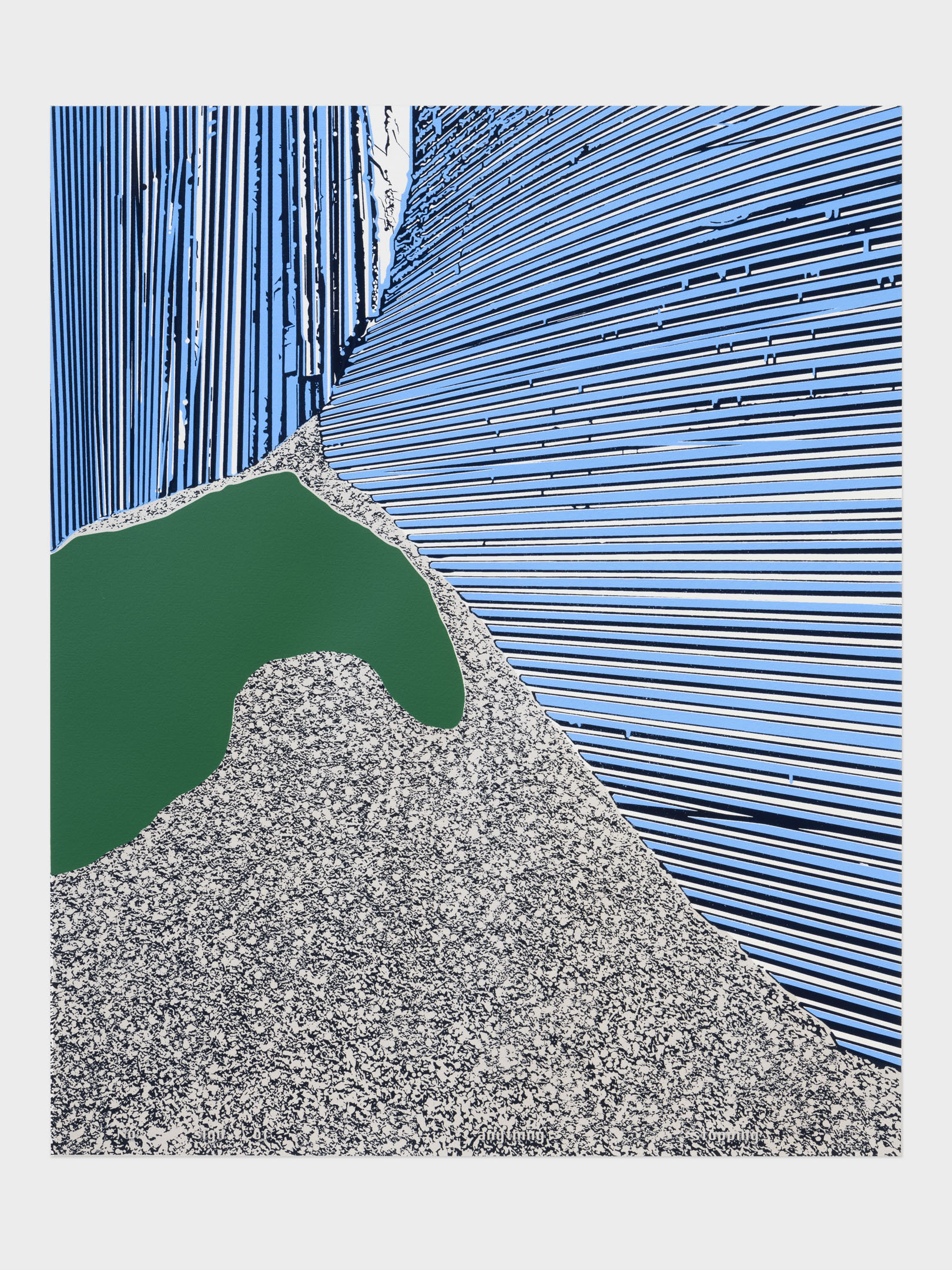

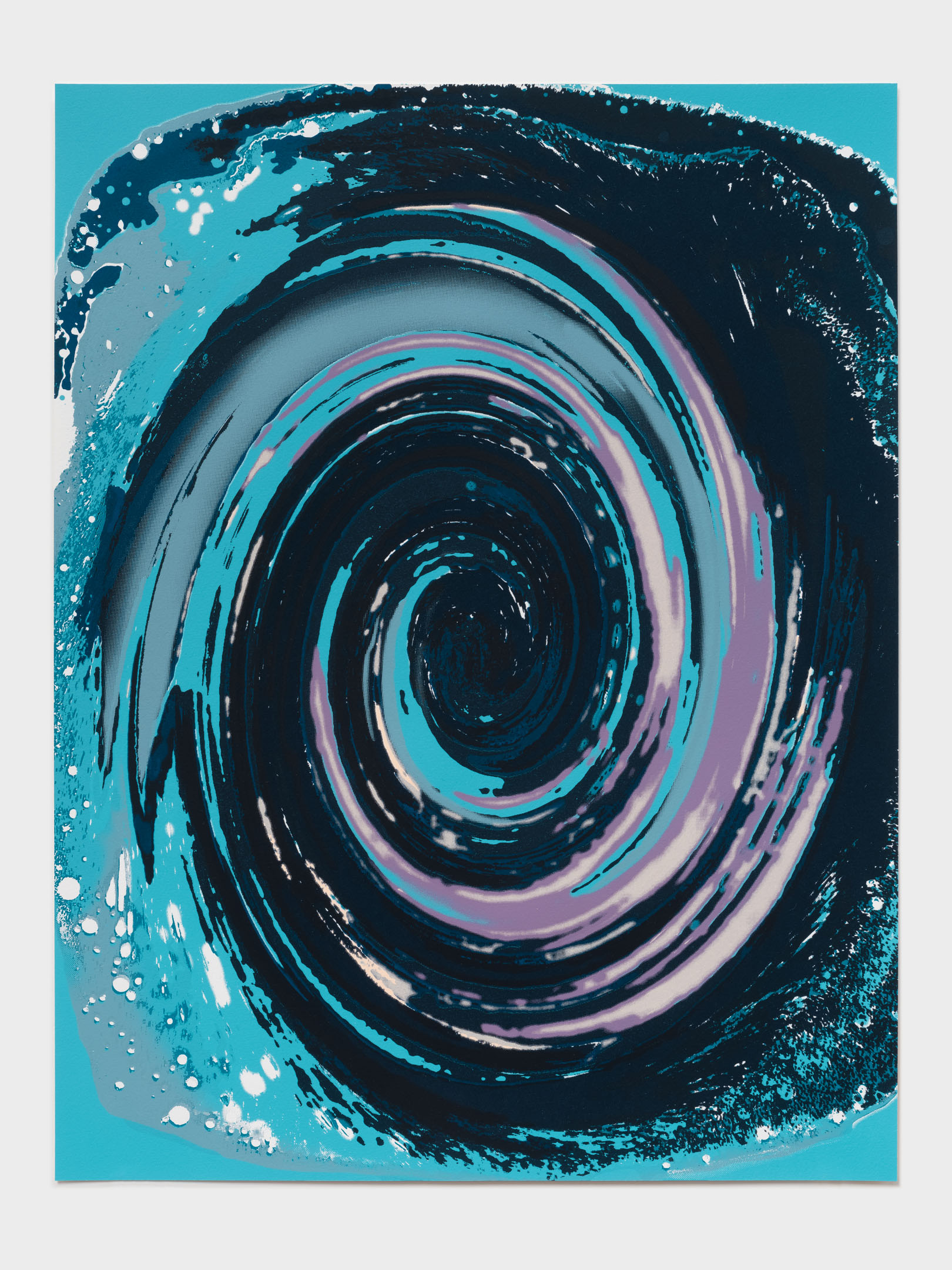

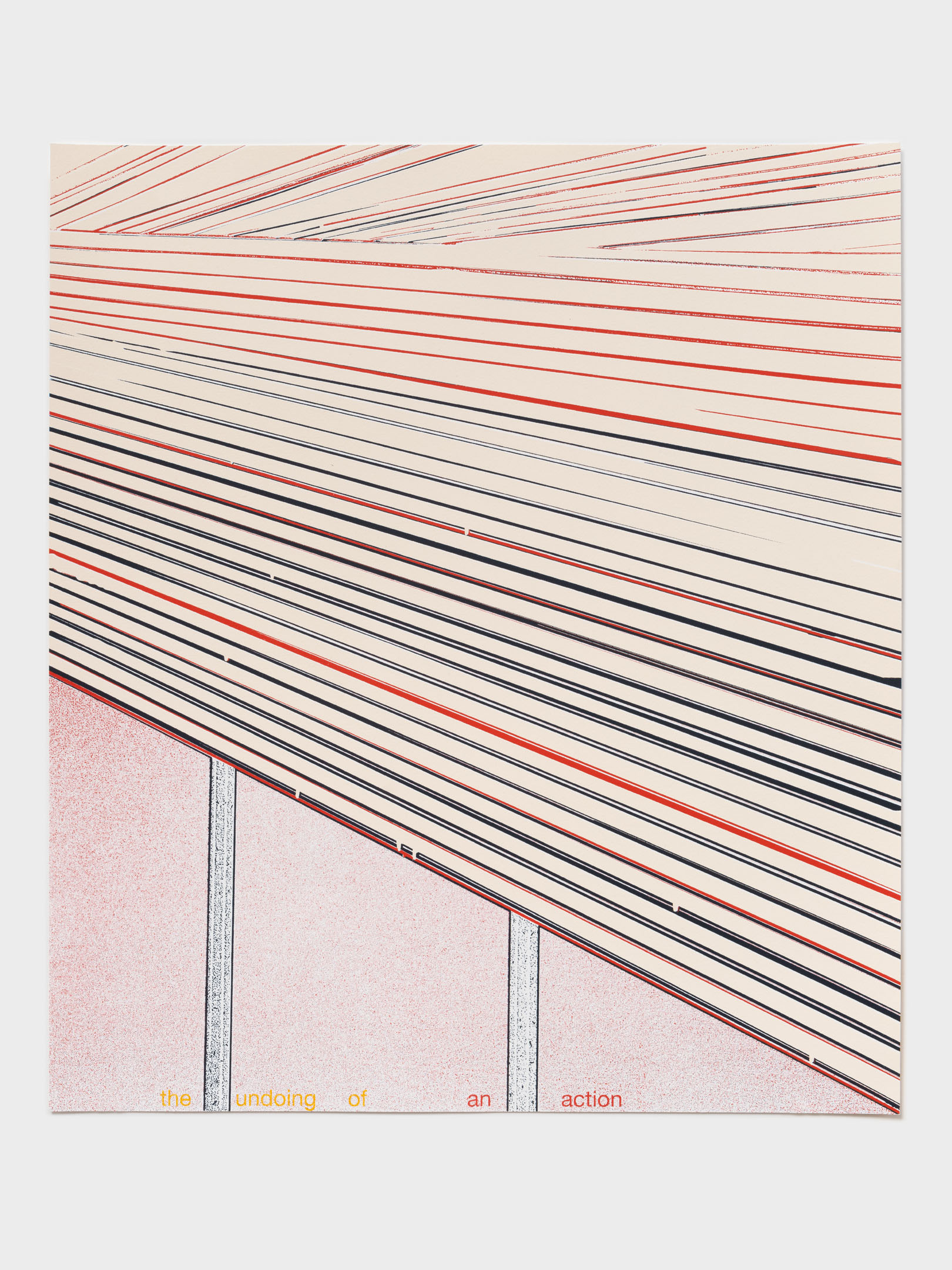

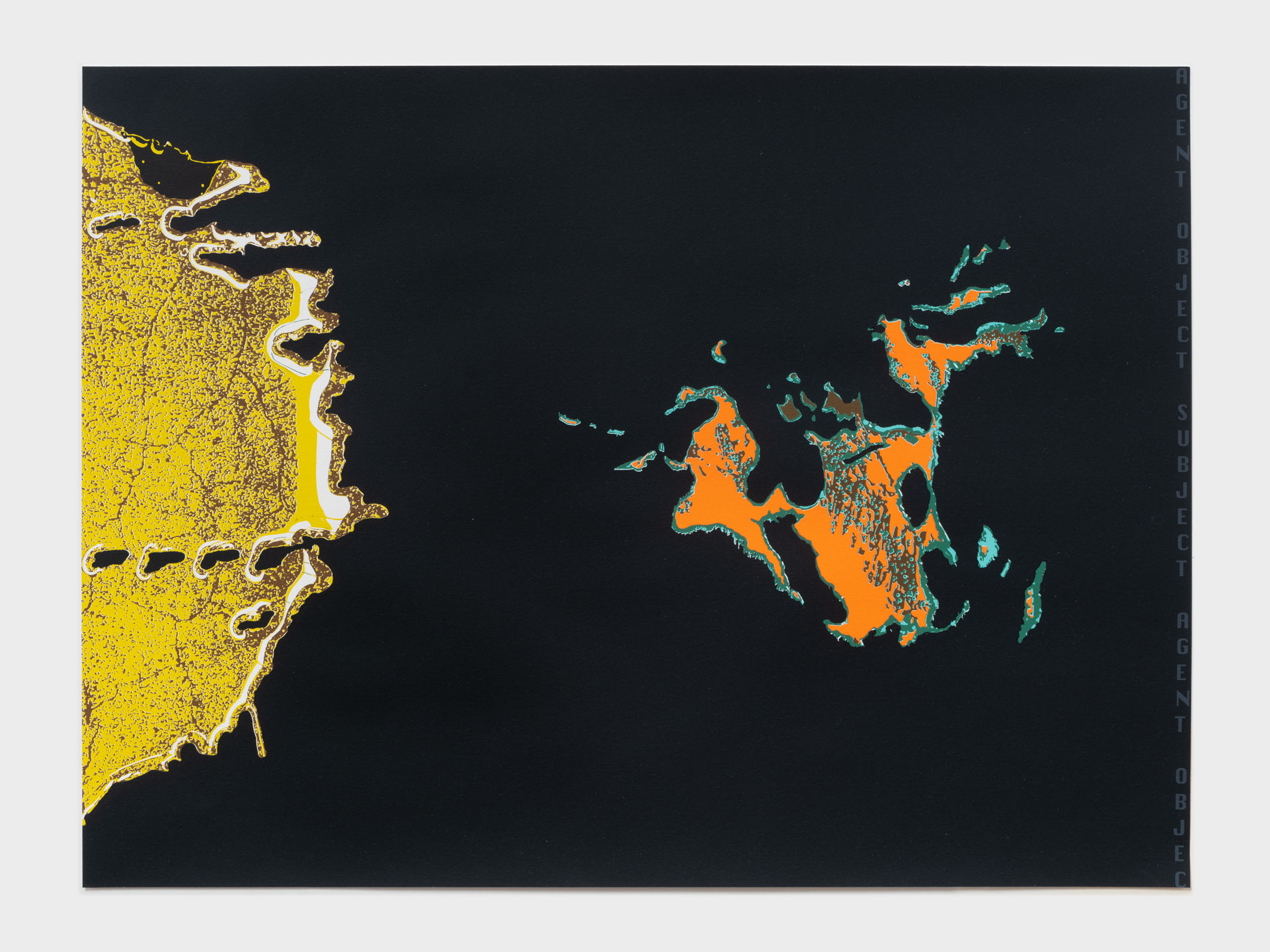

Westwood’s images initially flow from the external world, haphazardly appearing from everyday life. The photographic ‘encounters’ that inform his work reflect the kind of ordinariness that is easily overlooked in our lives, but that can surface through associations, feelings, and awareness’s within us. For Westwood, photographs represent fragments that comprise our lives, that can be seen as something recognisable that might equally be sensed as something unfamiliar. Westwood has a certain awareness that ordinary moments can somehow feel intense – that water travelling at speed down a sink may be as visceral an experience within one’s body, as it is also simply prosaic. Text and language are likewise ‘felt’ experiences that can shift instantaneously in our minds from the routine to the peculiar.

Westwood’s screen-prints utilise overlayered colours and textures in such a manner that only a trace of the original subject remains, what we are left with is something we feel we ought to recognise, something we feel we would know if only we could grasp just a little bit more.

Julia Powles and Peter Westwood are interested in how knowledge is formed. For both artists knowledge, or understanding, is something that must necessarily remain only partially articulated - semi-spoken words and ambiguous motifs are offered up for others to interpret and complete. These artists would suggest that knowingness arises within our bodies through experience and sensation as much as it is grasped within our minds.

While we can draw visual connections between the use of imagery and text in both Powles and Westwood’s works, less obvious is the way that they both mine their childhoods and unconscious selves for subject matter. The types of knowledge and understanding formed via our childhood experiences is uniquely felt and often profound in one’s life, as it comes from a time when our encounters are both bodily and psychologically felt, yet unexamined.

Language is an imprecise tool, and how well we can ever communicate our thoughts and ideas to others is uncertain. Devising text as tapestries, Powles formed sentences that are personal, having surfaced from specific events in her life – but while her sentences are particular, they correspondingly suggest the universalism of a homily like` ‘home sweet home’. Made from thread that is left over from other people’s projects, Powles never plans these works; the ordering of the words and final sentence arises while she is making them, allowing the very slowness of the process to help form her thoughts into words. Similarity her large-scale textile works have the appearance of formal abstraction yet are in fact derived from Venn diagrams of her complex family structure, again surfacing through conscious and unconscious awareness’s.

Westwood’s images initially flow from the external world, haphazardly appearing from everyday life. The photographic ‘encounters’ that inform his work reflect the kind of ordinariness that is easily overlooked in our lives, but that can surface through associations, feelings, and awareness’s within us. For Westwood, photographs represent fragments that comprise our lives, that can be seen as something recognisable that might equally be sensed as something unfamiliar. Westwood has a certain awareness that ordinary moments can somehow feel intense – that water travelling at speed down a sink may be as visceral an experience within one’s body, as it is also simply prosaic. Text and language are likewise ‘felt’ experiences that can shift instantaneously in our minds from the routine to the peculiar.

Westwood’s screen-prints utilise overlayered colours and textures in such a manner that only a trace of the original subject remains, what we are left with is something we feel we ought to recognise, something we feel we would know if only we could grasp just a little bit more.