Staring back at the world, 2013

Boutwell Draper Gallery, Sydney, Australia

The Waiting Places

The spaces depicted in this group of works are familiar to us, and yet Westwood’s treatment reveals them to be deeply mysterious and perhaps ultimately unknowable. These yards, supermarkets, docking-bays, waiting rooms, lots, terminals, hospitals, foyers and lobbies are the spaces in which we spend a good proportion of our lives, passing through, or marking time on our way to the next ports of call. And yet we barely register them as we drift through, always seemingly on our way to somewhere else. Their omnipresence renders them invisible. Do we ever pause to consider what effect these efficient and efficiently blank spaces have on us? How are we shaped by these vast ‘unnoticed’ structures that play so large a role in our lives?

Westwood has written in relation to this exhibition that: “We stare at the world and the world looks back… we exist within passivity, a state formed through a condition based in viewing, in looking on, consuming, enacting and partaking through inaction.”

There are certain spaces and places that especially engender this passivity within us. These transitory spaces in which we endlessly wait throughout our lives lull us with their unvarying homogeneity. Our experience within them is universal and unvarying: that is their sole purpose.

There are three paintings in the exhibition on the theme of planes and airports. Across the globe, from Melbourne to Mumbai, from Rio to Reykjavík, airports have the same appearance and functionality. We know where we are with them; and they know where they are with us. We arrive, we wait, and we depart, only to arrive and wait and depart from another, identical, place. In his 1997 essay, ‘The Ultimate Departure Lounge’, the British writer J. G. Ballard wrote:

In Out There (2013), we experience the aero-dreamscape from the vantage point of an observation lounge. We look across at another section of the lounge, glimpsed through streaked plate glass. We take in the painterly slabs of brightly-lit tarmac, which bleaches out and dissolves beneath the implacable black void of the night sky. The edges of the airport architecture are scuffed and scumbled, apparently in the process of dematerialising even as we register them. This is a place of anxiety; it is in flux, permanently in the state of becoming, or dissolving. In Transit Zone (2013), the sense of anxiety is continued. A plane waits eternally on the depopulated runway for its never-arriving passengers to come and give it purpose. A storm is approaching. Blossoms of oil and diesel bloom tropically drift across the runway as the reassuring markers of airport functionality devolve: the once-vital signifiers of runway ground lines are here only as practical as the various technical, painterly, smears and swipes with which Westwood constructs his painted airport. In On the inside (2013), we are transported inside a passenger plane. The claustrophobic interior glows womb-like and red. From our position, wedged in our Economy seat, beneath the luggage rack, we witness on the screen above us the globally-understood mime show of an airline safety demonstration. Here, Westwood contemplates the nature of looking, and the hierarchical importance attached to ‘official’ visual information. We look at the painting in which we are afforded, in cinematic-style, a passenger’s point-of-view. We, the viewer/passenger, then gaze at the ‘important’ image on the screen; this visual message is repeated on another screen, further down the aisle, and we know from experience that there are dozens more, out of view. The only ‘real’, figure within this painted cabin denies the purpose of the communication by looking away from the screens. We also look away from the screens in order to acknowledge the man, thereby becoming implicated in the complexity of reception and denial. Perhaps we will even identify with the man at a base level: all plane travellers will know the guilty pleasure and false optimism of paying scant heed to the potentially life-saving information being delivered, over our heads, while we wait impatiently to be ferried to our important destinations. The identical aero-pods we briefly inhabit on our journeys are instantly forgettable spaces in which we wait, suspending real time until we once again step onto the tarmac and re-enter our lives.

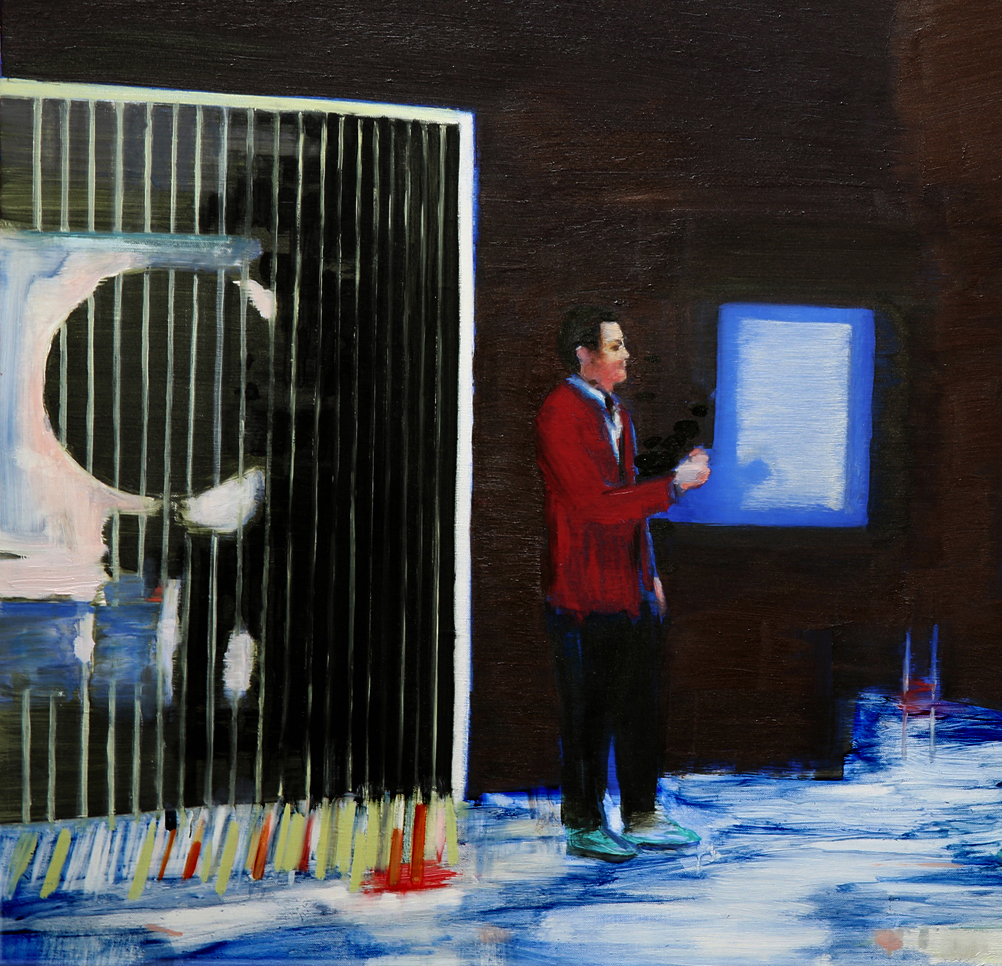

The womb-like interior is also evident in the painting Looking (2012), and the same investigation into ways of seeing is employed. In a mysterious crimson room, whose main function is indeterminate, a small group of people waits in front of a screen, upon which is projected an undefined but vaguely figurative image. A mirror stands to the left of the group and, mystifyingly, all appear to be ignoring the screen and gazing into it, with the exception of a white haired man who implicates the viewer of the painting in the action directly, by staring out at us. We are therefore observed as we observe. The conundrum of the image is forever unresolved, embedded as it is in the various layers of looking and the endless, invisible, cross-hatching of sightlines that dart between the real, actual, viewer and the viewers who are frozen within the narrative.

The spaces depicted in this group of works are familiar to us, and yet Westwood’s treatment reveals them to be deeply mysterious and perhaps ultimately unknowable. These yards, supermarkets, docking-bays, waiting rooms, lots, terminals, hospitals, foyers and lobbies are the spaces in which we spend a good proportion of our lives, passing through, or marking time on our way to the next ports of call. And yet we barely register them as we drift through, always seemingly on our way to somewhere else. Their omnipresence renders them invisible. Do we ever pause to consider what effect these efficient and efficiently blank spaces have on us? How are we shaped by these vast ‘unnoticed’ structures that play so large a role in our lives?

Westwood has written in relation to this exhibition that: “We stare at the world and the world looks back… we exist within passivity, a state formed through a condition based in viewing, in looking on, consuming, enacting and partaking through inaction.”

There are certain spaces and places that especially engender this passivity within us. These transitory spaces in which we endlessly wait throughout our lives lull us with their unvarying homogeneity. Our experience within them is universal and unvarying: that is their sole purpose.

There are three paintings in the exhibition on the theme of planes and airports. Across the globe, from Melbourne to Mumbai, from Rio to Reykjavík, airports have the same appearance and functionality. We know where we are with them; and they know where they are with us. We arrive, we wait, and we depart, only to arrive and wait and depart from another, identical, place. In his 1997 essay, ‘The Ultimate Departure Lounge’, the British writer J. G. Ballard wrote:

Airports have become a new kind of discontinuous city… I suspect that the airport will be the true city of the 21st century. The great airports of the planet are already the suburbs of an invisible world capital, a virtual metropolis whose faubourgs are named Heathrow, Kennedy, Charles de Gaulle, Nagoya, a centripetal city whose population forever circles its notional centre, and will never need to gain access to its dark heart.1

In Out There (2013), we experience the aero-dreamscape from the vantage point of an observation lounge. We look across at another section of the lounge, glimpsed through streaked plate glass. We take in the painterly slabs of brightly-lit tarmac, which bleaches out and dissolves beneath the implacable black void of the night sky. The edges of the airport architecture are scuffed and scumbled, apparently in the process of dematerialising even as we register them. This is a place of anxiety; it is in flux, permanently in the state of becoming, or dissolving. In Transit Zone (2013), the sense of anxiety is continued. A plane waits eternally on the depopulated runway for its never-arriving passengers to come and give it purpose. A storm is approaching. Blossoms of oil and diesel bloom tropically drift across the runway as the reassuring markers of airport functionality devolve: the once-vital signifiers of runway ground lines are here only as practical as the various technical, painterly, smears and swipes with which Westwood constructs his painted airport. In On the inside (2013), we are transported inside a passenger plane. The claustrophobic interior glows womb-like and red. From our position, wedged in our Economy seat, beneath the luggage rack, we witness on the screen above us the globally-understood mime show of an airline safety demonstration. Here, Westwood contemplates the nature of looking, and the hierarchical importance attached to ‘official’ visual information. We look at the painting in which we are afforded, in cinematic-style, a passenger’s point-of-view. We, the viewer/passenger, then gaze at the ‘important’ image on the screen; this visual message is repeated on another screen, further down the aisle, and we know from experience that there are dozens more, out of view. The only ‘real’, figure within this painted cabin denies the purpose of the communication by looking away from the screens. We also look away from the screens in order to acknowledge the man, thereby becoming implicated in the complexity of reception and denial. Perhaps we will even identify with the man at a base level: all plane travellers will know the guilty pleasure and false optimism of paying scant heed to the potentially life-saving information being delivered, over our heads, while we wait impatiently to be ferried to our important destinations. The identical aero-pods we briefly inhabit on our journeys are instantly forgettable spaces in which we wait, suspending real time until we once again step onto the tarmac and re-enter our lives.

The womb-like interior is also evident in the painting Looking (2012), and the same investigation into ways of seeing is employed. In a mysterious crimson room, whose main function is indeterminate, a small group of people waits in front of a screen, upon which is projected an undefined but vaguely figurative image. A mirror stands to the left of the group and, mystifyingly, all appear to be ignoring the screen and gazing into it, with the exception of a white haired man who implicates the viewer of the painting in the action directly, by staring out at us. We are therefore observed as we observe. The conundrum of the image is forever unresolved, embedded as it is in the various layers of looking and the endless, invisible, cross-hatching of sightlines that dart between the real, actual, viewer and the viewers who are frozen within the narrative.

As with airports, our shopping experiences are generic across the western world. As we labour our trolleys down the aisles of our identical supermarkets and mega-malls we are confirmed in the warm glow of certainty born of familiarity. As with air travel, nothing unexpected may be allowed to interrupt the smooth advance and embrace of consumerism. In No plan #2 (2012), the shoppers dissolve within the cold silver shimmer of a kind of shopping-cathedral. Their seemingly trance-like wanderings belie the title of the painting. Their individuality blurs and melts amidst the dazzling shards of neon and they become one with the self-fulfilling prophesy of consumerism. In the second of these shopping paintings, No Plan, we encounter a shopper purposefully striding with bag and trolley through a sprawling shopping-barn. The facial features are obscured and the gender is unspecified. Colours bleach out across the blank, neon-lit interior and architectural features soften under painterly slabs and swipes. The blue and orange floral blobs that decorate the shopper’s shirt are the same blue and orange blobs that mark out the background information at the far end of the supermarket so the shopper’s identity has thus been negated and, so far as it exists, is merely a byproduct of the all-engulfing consumer machine. To paraphrase the old dictum: ‘You Are What You Buy’.

The painting The last time (2013) deals with the fractured, ambiguous relationship we have with nature. Our experience of it is, more often than not, as something we have to pass through on our way to get to somewhere else. We commonly have a more ‘intimate’ relationship with nature through looking at historical landscape paintings or from viewing it on television or in movies, for it is on those friendly screens that we are able to safely observe this vast, wild, unpredictable thing, which lurks just outside our door. Again, this painting places us in a space of anxiety because the signifiers of things to be looked at and our expectations of how we should perceive them have been eroded. Several layers of reality jostle for primacy within the picture and every element presented is a simulacrum. We are inside and we are outside, simultaneously: the central woodland glade may be a painting, a film projected onto a screen, or an ‘actual’ view of nature through a window or portal; above this hangs a spotlit poster whose meaning has been deconstructed through its devolution into a piece of modernist abstraction; is the floor in the foreground carpeted, or is it just carpeted with the autumn leaves of the forest? Perhaps it is both. Suffusing the whole image is the clash of the romantic past with the industrial present, as the functional mechanics of air-conditioning ducts and metallic light slabs hang above the view of the forest like the sword of Damocles.

In Martin Amis’ 2002 essay, ‘The Second Plane’, about the attack on New York’s Twin Towers, he wrote that ‘an edifice so demonstrably comprised of concrete and steel would also become an unforgettable metaphor’.[2] He went on to say that the moment the buildings collapsed was ‘the apotheosis of the postmodern era – the era of images and perceptions.’ Is it now even possible for us to view any demolished building without images from that primary über-demolition muscling into our consciousness? From this point on every building’s demolition and the aftermath of its fall – the crushed concrete, twisted girders and rubble-filled craters - come with a special connotation attached. There are various paintings about demolition in the exhibition. As with the other pictures in the show a number of readings are possible. These broken buildings also have metaphorical potential; they are perhaps ciphers embodying the idea of change, whether positive or negative; or perhaps they are they frozen, half-standing, moments of entropy, forever poised between being and not being. The sliced, flattened frontage of the apartment block in Not too close, not too far could as easily be a painted theatre backdrop as an actual building; the painterly blobs describing the rubble spilling about its foundations are also those depicting the cluster of people observing the spectacle of its demise. The buildings in Next, next, next, next …(2011) have been flattened out across a grid-like picture plane, a black void stretches across their baseline to facilitate their imminent nothingness; their existence and non-existence is here solely dependent on the ideals of modernist abstraction. In Nowhere (2012), the half-demolished structures crouched around a central crater evoke the magical artificiality of theatrical sets constructed on a stage. In the middle-ground the seemingly familiar furniture of the de-construction turns out to be no more than deft, painterly, con-struction. The dark grey space that runs across the bottom of the image emphasises its closed off separateness from the actual.

But, in a sense, all of the paintings in the exhibition exist in a ‘closed off’ and ‘separate’ universe. Each image exists in a state simultaneously of commencement and denouement. The images remind us that ‘to look’ is rarely ‘to know’. In any event, we will have abundant time to contemplate all of this as we fritter away our hours in the next waiting room, on the way to somewhere else.

Notes:

The painting The last time (2013) deals with the fractured, ambiguous relationship we have with nature. Our experience of it is, more often than not, as something we have to pass through on our way to get to somewhere else. We commonly have a more ‘intimate’ relationship with nature through looking at historical landscape paintings or from viewing it on television or in movies, for it is on those friendly screens that we are able to safely observe this vast, wild, unpredictable thing, which lurks just outside our door. Again, this painting places us in a space of anxiety because the signifiers of things to be looked at and our expectations of how we should perceive them have been eroded. Several layers of reality jostle for primacy within the picture and every element presented is a simulacrum. We are inside and we are outside, simultaneously: the central woodland glade may be a painting, a film projected onto a screen, or an ‘actual’ view of nature through a window or portal; above this hangs a spotlit poster whose meaning has been deconstructed through its devolution into a piece of modernist abstraction; is the floor in the foreground carpeted, or is it just carpeted with the autumn leaves of the forest? Perhaps it is both. Suffusing the whole image is the clash of the romantic past with the industrial present, as the functional mechanics of air-conditioning ducts and metallic light slabs hang above the view of the forest like the sword of Damocles.

In Martin Amis’ 2002 essay, ‘The Second Plane’, about the attack on New York’s Twin Towers, he wrote that ‘an edifice so demonstrably comprised of concrete and steel would also become an unforgettable metaphor’.[2] He went on to say that the moment the buildings collapsed was ‘the apotheosis of the postmodern era – the era of images and perceptions.’ Is it now even possible for us to view any demolished building without images from that primary über-demolition muscling into our consciousness? From this point on every building’s demolition and the aftermath of its fall – the crushed concrete, twisted girders and rubble-filled craters - come with a special connotation attached. There are various paintings about demolition in the exhibition. As with the other pictures in the show a number of readings are possible. These broken buildings also have metaphorical potential; they are perhaps ciphers embodying the idea of change, whether positive or negative; or perhaps they are they frozen, half-standing, moments of entropy, forever poised between being and not being. The sliced, flattened frontage of the apartment block in Not too close, not too far could as easily be a painted theatre backdrop as an actual building; the painterly blobs describing the rubble spilling about its foundations are also those depicting the cluster of people observing the spectacle of its demise. The buildings in Next, next, next, next …(2011) have been flattened out across a grid-like picture plane, a black void stretches across their baseline to facilitate their imminent nothingness; their existence and non-existence is here solely dependent on the ideals of modernist abstraction. In Nowhere (2012), the half-demolished structures crouched around a central crater evoke the magical artificiality of theatrical sets constructed on a stage. In the middle-ground the seemingly familiar furniture of the de-construction turns out to be no more than deft, painterly, con-struction. The dark grey space that runs across the bottom of the image emphasises its closed off separateness from the actual.

But, in a sense, all of the paintings in the exhibition exist in a ‘closed off’ and ‘separate’ universe. Each image exists in a state simultaneously of commencement and denouement. The images remind us that ‘to look’ is rarely ‘to know’. In any event, we will have abundant time to contemplate all of this as we fritter away our hours in the next waiting room, on the way to somewhere else.

Steve Cox—2 April, 2013

Steve Cox is an artist, writer and academic based in Melbourne.

Notes:

- J. G. Ballard, ‘The Ultimate Departure Lounge’, The Observer, September 14th, 1997.

- Martin Amis, ‘The Second Plane’, The Guardian, September 18th, 2001.