Caught by surprise, 2022

A survey of recent work at Galerie der HBK, BraunschweigBraunschweig University of Art, Germany

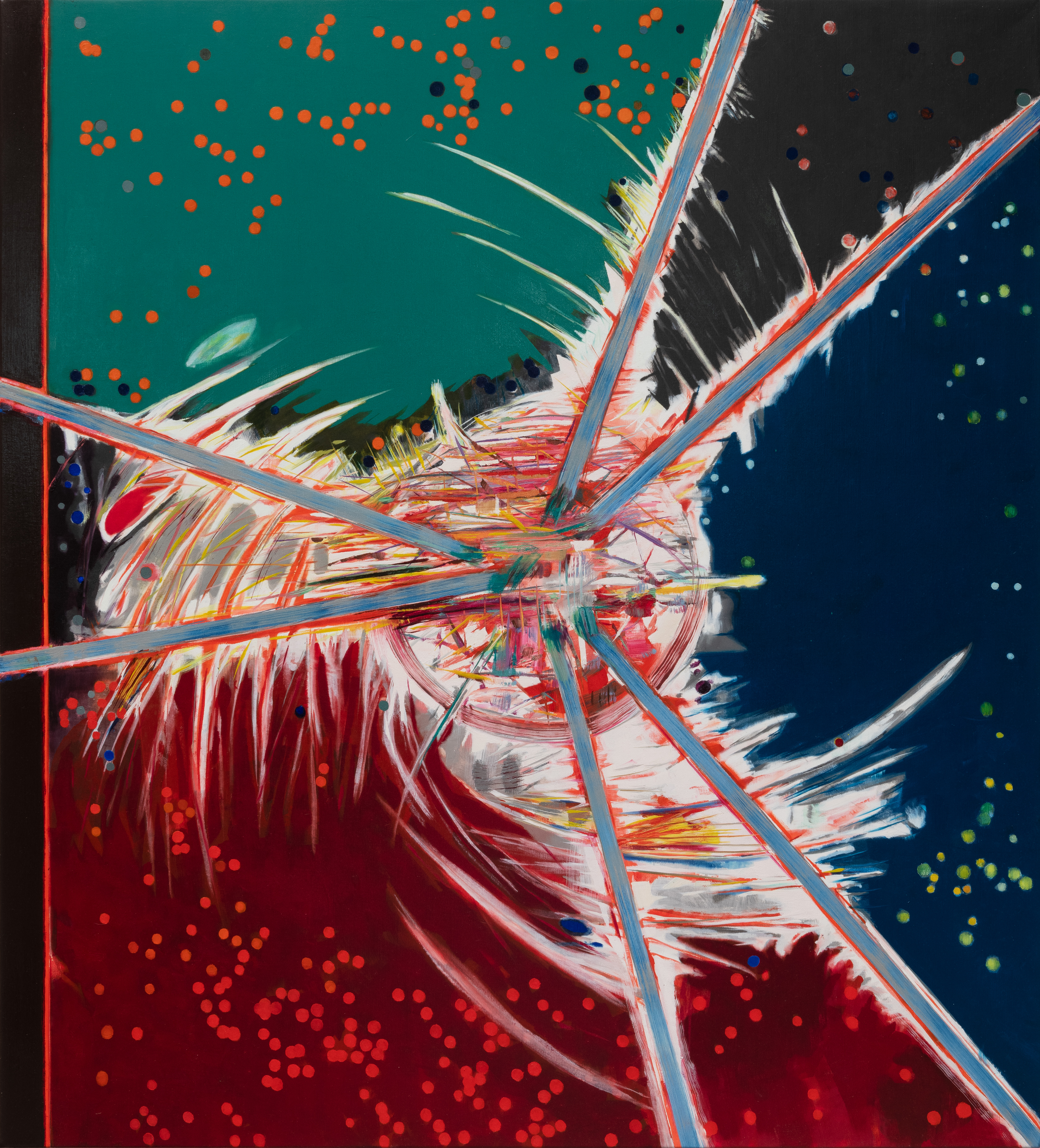

fig 1. Installation view main gallery

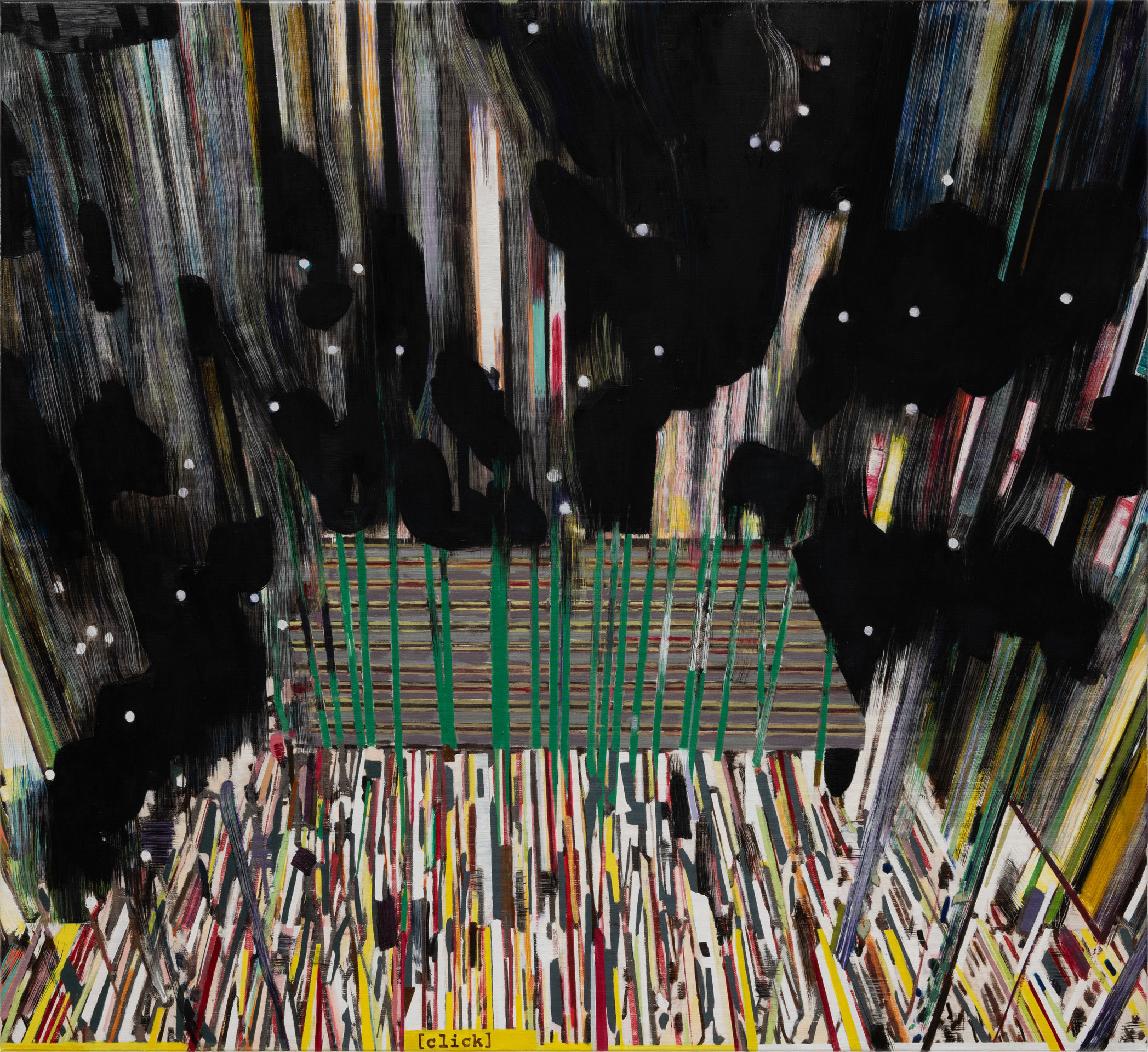

fig 2. Installation view

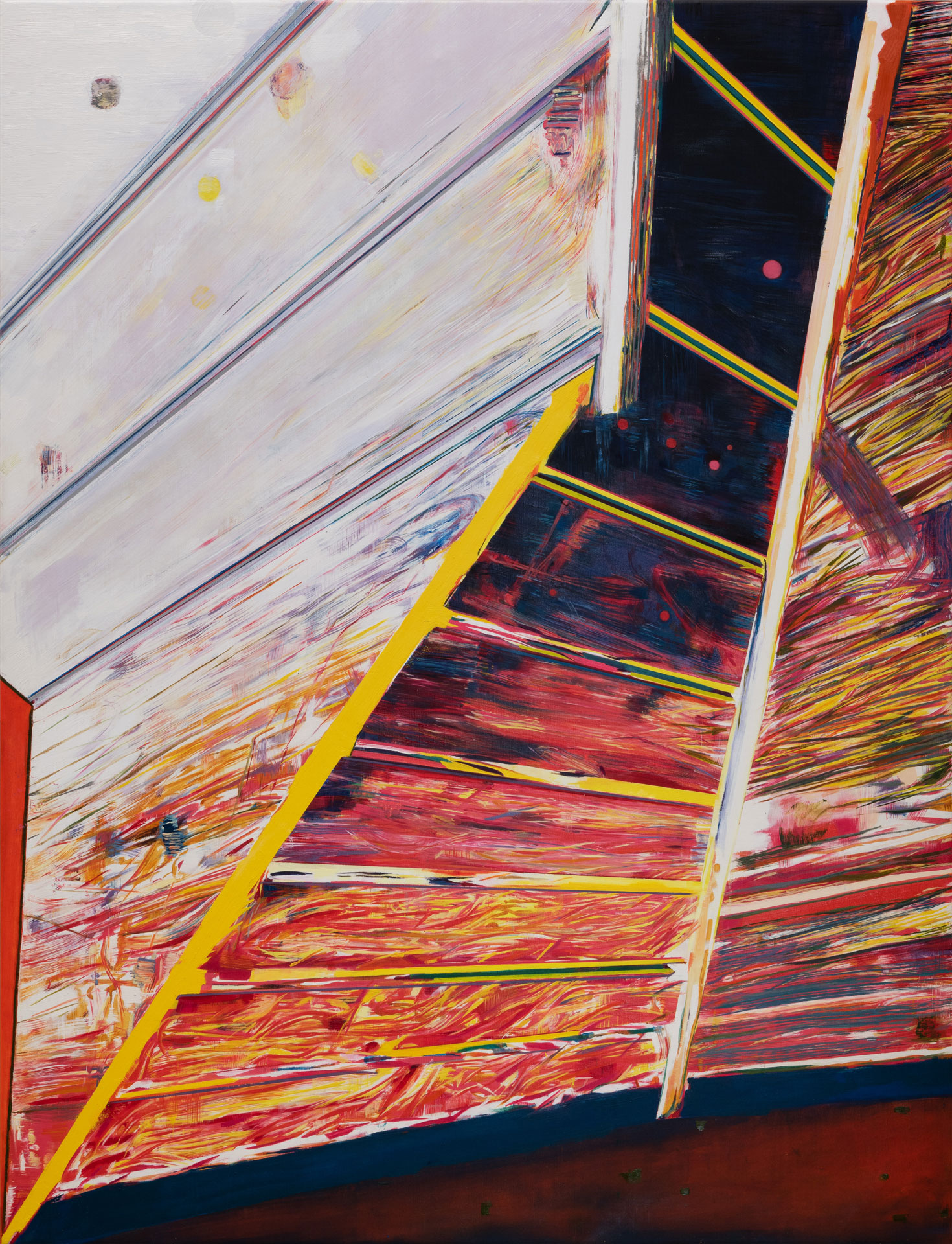

fig 3. Installation view

fig 4. Window text

All of this is true, most of it happened. Some thoughts on Peter Westwood’s Caught by Surprise.

When we first met to discuss his exhibition at Braunschweig University of Art, Peter Westwood suggested that if he was to succinctly describe the body of work he would display, he would say it existed on ‘an undulating plane of re-formation’.1 As we talked, this premise (and its multiple connotations) seemed at once precarious and liberating. There was no sense that art, and specifically painting, functioned for him as a vehicle for critique or as an agent of change, but rather that it was a means to apprehend the feeling of where we are and of the world we are in, and what the experience of our times, with all its complexity and unpredictability, might look like.

This mode of expression is a long way from Westwood’s beginning as an artist. It may surprise newcomers to his work to learn that he left art school in the 1970s as a photorealist: that most exacting and, some would say, dispassionate category of image-makers—beguilingly precise and intimidatingly conscious, yet in some ways at arm’s length from real life. His work epitomised the style and met with rapid commercial and institutional success, but Westwood’s personal investment was short-lived. Two years later he ‘went hunting’ for an alternative, a form of expression that leaned into the experiential, bodily and psychological, and he has explored this generative ground ever since. ‘My practice shifted until it was closer to me’, he observed.

This is not to suggest that Westwood’s painting operates in a purely instinctual way; on the contrary, his practice is underpinned by a continual, curious investigation of the human condition and as such contemporaneity and its agents—the social and political realms—are pervasive. And while his works don’t explicitly picture issues and events of our times, they are overwhelmingly responsive to and conditioned by them.

Take No change, much the same, 2017, for instance. The image has two distinct zones, one fugitive and indeterminate, and the other with the appearance of a boardwalk beginning outside the picture’s boundaries and leading to an unseen destination. The small horizontal stripes of the built structure are unexpectedly overlaid with large stripes of red, white and blue that are typical of a national flag, bringing with them the various revolutionary and ambivalent political associations of the tricolour. The impression is one of ongoingness yet uncertainty, of a transition that is inadequate or incomplete. In Field of sorrow (untethered), 2021, the familiar and unfamiliar are similarly seen to be co-existing, with the central motif of a European thistle growing in a visceral, blood-red soil that supports a host of unidentifiable other vegetation. The composition is overlaid with a sequence of blue threads, suggestive of another, unknown dimension while signalling contradictory notions of confinement or of unravelling.

A further work, I mixed up the idea of space between humans and objects, 2020, features a gridded object that began as an image of a museum trolley. Now immobile and sunk to the bottom of the picture plane, it takes on a perplexing spatial ambiguity, the curves and lines of the form rendered flatly and pushing and pulling between fore- and mid-ground. The caption at the top of the painting re-calibrates the image as a kind of illustration or reportage. ‘Without the text it would be personal, not socio-political’, Westwood observes.

Stylistically there is little that visually binds these works together, or that even suggests they are by the same artist. Instead, it becomes apparent that in his intuitive and practice-led approach Westwood is open to precognitive awareness, and his process is one of shifting thoughts and feelings from the inner self to the exterior world.2 Implicit is the possibility, as Julia Powles has proposed, ‘that paint can give form to an alternative type of knowledge’.3

Westwood usually begins a new painting by roughly sketching in an image from a photograph—a snapshot on his phone or something that has appealed for any subjective reason—to establish the foundational form. Then he stops working from the photo and feels his way forward, building in observations about the world and trusting the image to lead him. Westwood paints like a collagist, deploying remnants and piecing things together until they coalesce. Yet there is a prescient quality to his paintings, in that they each feel like a perception as much as being an action in the world. Around two-thirds of the way into the image-making words begin to form and a title arrives. He continues to work until the picture doesn’t need more accumulations, and stops when he looks around and feels that there isn’t more to do.

In concert with his description of an ‘undulating plane of re-formation’, Westwood sees painting as an unstable art form, and the act of painting as a mutable experience, so there is a corresponding sense that the real content of his images lies beyond the works themselves. This intellectual sensibility is derived both from personal tendencies and beliefs and his reading of contemporary philosophy and theories of art via James Elkins, Isabelle Graw, Boris Groys, David Joselit and Peter Osborne, to name a few. Like Graw, Westwood sees painting as an adjustable, adaptive medium eminently suited and attuned to change. More than a language, it ‘promotes vitalities, aliveness and power, through its very presence’.4

The exhibition Caught by Surprise brings together examples of Peter Westwood’s work from the past five years. After some time in the planning its delivery has been subject to rescheduling and unpredictability due to the pandemic, an apt corollary to the nature of the project itself. Its seductive title attends to sensation and to a moment in time and has applications for both maker and viewer. ‘I’m surprised by the feelings in the paintings’, he told me in the studio as we looked at the canvases, as if the works had taken on their own independent lives and the reactions and emotions within them were no longer his.

The audience experience of the exhibition is a testing, active one, for although it represents the work of one artist it has the look of a group show with its diverse imagery, inconstant palette, and uneasy truce between figuration and abstraction. The works are unmistakeably alive to perception and the world of appearances, yet there is a palpable idea of disruption both within the paintings and between them. Meaning and associations form, shift, and even collapse in individual works as well as across them, requiring adjustment for the eye and mind as patterns of appearance, style and subject matter are difficult to locate. To further amplify the exhibition’s heterogeneity, Westwood has placed a blank wall within the gallery. The device creates a physical tension by interrupting sightlines and regulating circulation, simulating his use of conscious and unconscious strategies within the paintings themselves.

While the exhibition may be read as a metaphor for the variability of contemporaneity, so too does it function as a space or atmosphere that has its own currency, in the temporal meaning of the word. Caught by Surprise has a start and end so that in planning it exists in the future, in occupancy it is in the present, and in closure it is in the past. This may seem like an obvious thing to point out, but for Westwood the concept of ‘coming into being’ pertains equally to the exhibition and its constituent parts. Each represents a creative action or practice that is internal unto itself until its products are released into the social world, at which point they become speculative, in a way—subject to who sees them, and when. Changeability and inconclusiveness are inherent to both, and the possibilities offered are further perceived or devised by the viewer. In Westwood’s words, ‘this uncertainty ultimately provides an experience of what I consider reflects and embodies the indeterminate temper of our times’.5 The works in the exhibition, then, are presented as both independent of what came before and after, and at the same time as an ambiguous whole.6

The incertitude and instability of living in the climate-affected, pandemic and war-ridden late-capitalist world is inescapable, and in so far as all painting is part of a socio-political continuum, Westwood’s inevitably yields to the outside realm. Yet he also sees our ever-changing present as a place of productive renewal and creative possibility, and his overarching project and preoccupation continues to be to try and harness the potential of painting as a sensory and ‘pre-purposeful’ indicator of our times.

When we first met to discuss his exhibition at Braunschweig University of Art, Peter Westwood suggested that if he was to succinctly describe the body of work he would display, he would say it existed on ‘an undulating plane of re-formation’.1 As we talked, this premise (and its multiple connotations) seemed at once precarious and liberating. There was no sense that art, and specifically painting, functioned for him as a vehicle for critique or as an agent of change, but rather that it was a means to apprehend the feeling of where we are and of the world we are in, and what the experience of our times, with all its complexity and unpredictability, might look like.

This mode of expression is a long way from Westwood’s beginning as an artist. It may surprise newcomers to his work to learn that he left art school in the 1970s as a photorealist: that most exacting and, some would say, dispassionate category of image-makers—beguilingly precise and intimidatingly conscious, yet in some ways at arm’s length from real life. His work epitomised the style and met with rapid commercial and institutional success, but Westwood’s personal investment was short-lived. Two years later he ‘went hunting’ for an alternative, a form of expression that leaned into the experiential, bodily and psychological, and he has explored this generative ground ever since. ‘My practice shifted until it was closer to me’, he observed.

This is not to suggest that Westwood’s painting operates in a purely instinctual way; on the contrary, his practice is underpinned by a continual, curious investigation of the human condition and as such contemporaneity and its agents—the social and political realms—are pervasive. And while his works don’t explicitly picture issues and events of our times, they are overwhelmingly responsive to and conditioned by them.

Take No change, much the same, 2017, for instance. The image has two distinct zones, one fugitive and indeterminate, and the other with the appearance of a boardwalk beginning outside the picture’s boundaries and leading to an unseen destination. The small horizontal stripes of the built structure are unexpectedly overlaid with large stripes of red, white and blue that are typical of a national flag, bringing with them the various revolutionary and ambivalent political associations of the tricolour. The impression is one of ongoingness yet uncertainty, of a transition that is inadequate or incomplete. In Field of sorrow (untethered), 2021, the familiar and unfamiliar are similarly seen to be co-existing, with the central motif of a European thistle growing in a visceral, blood-red soil that supports a host of unidentifiable other vegetation. The composition is overlaid with a sequence of blue threads, suggestive of another, unknown dimension while signalling contradictory notions of confinement or of unravelling.

A further work, I mixed up the idea of space between humans and objects, 2020, features a gridded object that began as an image of a museum trolley. Now immobile and sunk to the bottom of the picture plane, it takes on a perplexing spatial ambiguity, the curves and lines of the form rendered flatly and pushing and pulling between fore- and mid-ground. The caption at the top of the painting re-calibrates the image as a kind of illustration or reportage. ‘Without the text it would be personal, not socio-political’, Westwood observes.

Stylistically there is little that visually binds these works together, or that even suggests they are by the same artist. Instead, it becomes apparent that in his intuitive and practice-led approach Westwood is open to precognitive awareness, and his process is one of shifting thoughts and feelings from the inner self to the exterior world.2 Implicit is the possibility, as Julia Powles has proposed, ‘that paint can give form to an alternative type of knowledge’.3

Westwood usually begins a new painting by roughly sketching in an image from a photograph—a snapshot on his phone or something that has appealed for any subjective reason—to establish the foundational form. Then he stops working from the photo and feels his way forward, building in observations about the world and trusting the image to lead him. Westwood paints like a collagist, deploying remnants and piecing things together until they coalesce. Yet there is a prescient quality to his paintings, in that they each feel like a perception as much as being an action in the world. Around two-thirds of the way into the image-making words begin to form and a title arrives. He continues to work until the picture doesn’t need more accumulations, and stops when he looks around and feels that there isn’t more to do.

In concert with his description of an ‘undulating plane of re-formation’, Westwood sees painting as an unstable art form, and the act of painting as a mutable experience, so there is a corresponding sense that the real content of his images lies beyond the works themselves. This intellectual sensibility is derived both from personal tendencies and beliefs and his reading of contemporary philosophy and theories of art via James Elkins, Isabelle Graw, Boris Groys, David Joselit and Peter Osborne, to name a few. Like Graw, Westwood sees painting as an adjustable, adaptive medium eminently suited and attuned to change. More than a language, it ‘promotes vitalities, aliveness and power, through its very presence’.4

The exhibition Caught by Surprise brings together examples of Peter Westwood’s work from the past five years. After some time in the planning its delivery has been subject to rescheduling and unpredictability due to the pandemic, an apt corollary to the nature of the project itself. Its seductive title attends to sensation and to a moment in time and has applications for both maker and viewer. ‘I’m surprised by the feelings in the paintings’, he told me in the studio as we looked at the canvases, as if the works had taken on their own independent lives and the reactions and emotions within them were no longer his.

The audience experience of the exhibition is a testing, active one, for although it represents the work of one artist it has the look of a group show with its diverse imagery, inconstant palette, and uneasy truce between figuration and abstraction. The works are unmistakeably alive to perception and the world of appearances, yet there is a palpable idea of disruption both within the paintings and between them. Meaning and associations form, shift, and even collapse in individual works as well as across them, requiring adjustment for the eye and mind as patterns of appearance, style and subject matter are difficult to locate. To further amplify the exhibition’s heterogeneity, Westwood has placed a blank wall within the gallery. The device creates a physical tension by interrupting sightlines and regulating circulation, simulating his use of conscious and unconscious strategies within the paintings themselves.

While the exhibition may be read as a metaphor for the variability of contemporaneity, so too does it function as a space or atmosphere that has its own currency, in the temporal meaning of the word. Caught by Surprise has a start and end so that in planning it exists in the future, in occupancy it is in the present, and in closure it is in the past. This may seem like an obvious thing to point out, but for Westwood the concept of ‘coming into being’ pertains equally to the exhibition and its constituent parts. Each represents a creative action or practice that is internal unto itself until its products are released into the social world, at which point they become speculative, in a way—subject to who sees them, and when. Changeability and inconclusiveness are inherent to both, and the possibilities offered are further perceived or devised by the viewer. In Westwood’s words, ‘this uncertainty ultimately provides an experience of what I consider reflects and embodies the indeterminate temper of our times’.5 The works in the exhibition, then, are presented as both independent of what came before and after, and at the same time as an ambiguous whole.6

The incertitude and instability of living in the climate-affected, pandemic and war-ridden late-capitalist world is inescapable, and in so far as all painting is part of a socio-political continuum, Westwood’s inevitably yields to the outside realm. Yet he also sees our ever-changing present as a place of productive renewal and creative possibility, and his overarching project and preoccupation continues to be to try and harness the potential of painting as a sensory and ‘pre-purposeful’ indicator of our times.

Lesley Harding

Artistic Director, Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne

June 2022

- All quotes by the artist are from conversations with the author on 22 October 2021 at RMIT University, Melbourne, and 6 May 2022 at the artist’s studio, North Melbourne.

- Peter Westwood, ‘Painting as a marker of change’, PhD thesis, School of Art, College of Design and Social Context, RMIT University, July 2021, p. 9.

- Julia Powles, ‘The poor hospital (passage and fate)’, Blockprojects Gallery, Melbourne, 2015.

- Ibid., p. 10.

- Ibid., p. 59.

- A coda to the exhibition of paintings is Westwood’s production in Braunschweig of several inscribed T-shirts, presented in a stack, that are available for visitors to take away. The idea serves as a metaphor for the exhibition itself: the constituent parts of the set will live on in the world in a fragmented way—worn and stored, seen and unseen over time, never to come together again.